Short of the entire bike industry turning to making bamboo-based bikes, can the industry ever build sustainability into its products? Erik Bronsvoort, author of Marginal Gains to a Circular Cycling Revolution argues that, with willpower to improve, we can…

Iam the proud owner of a 2012 Cannondale SuperSix Evo. A first-generation version of the frameset with a weight-saving clear coat and Cannondale green detail- ing on the frame, seatpost and stem. It features a limited- edition SRAM RED ten-speed groupset with the same green instead of red details. I had been waiting for some- thing special like this for a while. Apart from the custom groupset, the frame design was a move away from the “stiffness is everything” designs to something more comfortable, lightweight, yet still stiff enough for a guy like Peter Sagan.

After eight years and some 40.000km, I am spending more and more time maintaining the bike. I really want to keep the green edition groupset intact. I managed to replace a worn part of the rear derailleur cage with a SRAM Force replacement part I accidentally found on a flea market. Some other parts of the groupset are worn, the crisp shifting is gone. A couple of weeks ago, the aluminium thread in the left crankarm cracked. SRAM 10- speed parts, let alone the limited edition, are no longer available. New 11 or 12 speed parts are incompatible.

I am facing a dilemma many cyclists face at some point: as compatible replacement parts run out, will I replace the whole groupset, or maybe even buy a new bike?

The truth is, I do not want either of them. I want to ride this bike for many more years. Not just because I genuinely love it. At least as important: I do not want to waste all the precious materials that together form this bike.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF INCOMPATIBILITY

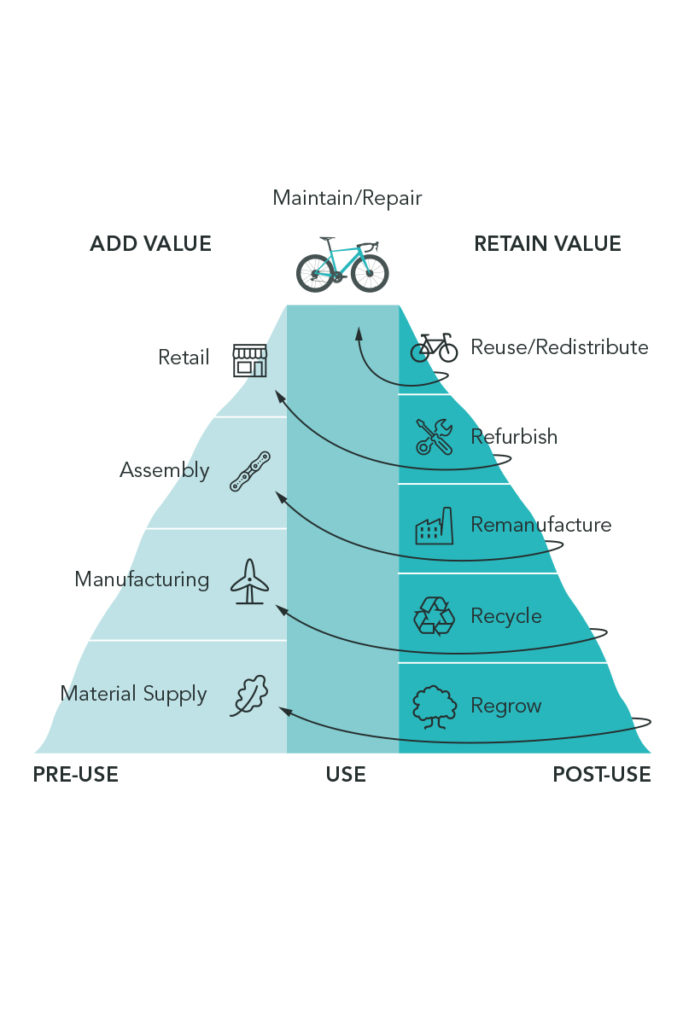

Our world, including the cycling industry, is running a linear economic system. We take raw materials from the earth, add value to it by manufacturing parts and then turn them into a bike. The consumer pays for this value, and uses the products for a while. The value is then quickly wasted once the bike’s parts are disposed of in the post-use phase.

Linear economy Value Hill

To make a profit in a linear economy, companies try to ‘sell more, sell faster’. The consequence is that we ‘waste more, and waste faster’. While creating the value and destroying the value, air, soil and oceans are polluted. Mining wrecks ecosystems and materials are lost forever once they end up on a landfill or in an incinerator.

Consumers like me are in no position to influence this system, apart from trying to make sure that products are well maintained and used as long as possible.

My dilemma is caused by what we identified as one of three “linear design incentives” that dominate the cycling industry: products are designed to be outdated.

The ‘designed to be outdated’ linear design strategy is very common in many industries. The computer and mobile phone industries offer clear examples. Every few years, a new model is introduced with more computer power and new interfaces between the device and, for example, a charger. The new interface requires new cables, making the old cables instantly worthless. Soft- ware updates are even worse culprits, as they are often also pushed to older generations of the product with less memory and computing power. The updates slow down the older models and reduce their battery life, forcing the consumer to buy a new one.

New generations of parts in the cycling industry cause the same problem. Backwards compatibility is not part of the general design principles. Instead, the change from Shimano 10-speed to 11-speed and, more recently, the introduction of the SRAM XD and Shimano Micro Spline cassette bodies have made many older generation wheelsets useless. The same goes for the rest of the driv- etrain: shifters, derailleurs, chains and cassettes become waste if one of the parts in the groupset fails and is no longer available as a replacement part. Aero seatposts and integrated stem/handlebars are only compatible to a certain type of frameset.

A CIRCULAR REVOLUTION

The challenge for the world of cycling is to make a shift towards a circular economic system. A world where bicy- cles, equipment and clothing are eventually made from renewable plant-based materials or reused and recycled parts. Where materials wearing from tyres or brake pads are biodegradable and lubricants provide valuable nutri- ents for the environment. Where pollution and waste are a thing of the past, and nature gets a chance to recover, so it can provide us with even nicer places to ride.

In such a circular cycling economy, materials will be in use longer because of longer-lasting designs, mainte- nance is easier, and wear indicators tell users when parts are worn and up for replacement. Repairs can be done efficiently and are part of manufacturers’ business models. Used bikes, bike parts, equipment and clothing are returned to their manufacturer, so they can reuse and refurbish parts and materials to make new products. Or, alternatively, materials are biodegradable, so they can become part of the circle of life again.

This system will require a different set of design strategies and business models to create and maintain the value of the materials. It will require all the creativity in the industry to get there. How will we get there, you wonder? By making a start. Instead of the linear design incentives, we propose four circular design incentives:

1 > Make it last forever

2 > Compatibility, adaptability & upgradability

3 > Ease of maintenance & repair

4 > Choosing the right materials

Making a profit with these design principles will require manufacturers to change their business models. In a book we have written about this subject we explain how consumers will buy a ‘Platform’: a frameset, seatpost/seat and stem/handlebar package perfectly fitted to their body and riding style. Because products last forever, this Platform can be either new or pre-used. Manufacturers will offer a buy-back guarantee to get their products back for another rider to use it.

Groupsets and wheelset will be combined into a ‘Powertrain’ and get a ‘pay-for-performance’ model. Users will pay a regular fee for the use of the product, not for the product itself. The manufacturer is responsible for making sure that the performance is guaranteed through smart designs and maintenance.

It would be a win-win-win situation: customers win because they are able to ride more reliable products that require less maintenance, the industry wins because it can create equal or more value with less material and, finally, the planet wins because there will no longer be any waste or pollution, and nature will get a chance to regenerate.