Cycling is green, but the bikes we ride are not. A possible fix might come from a most unlikely source.

Article on Escape Collective, written by Ronan Mc Laughlin

UCI equipment rules could hold the key to sustainability.

The hunt for marginal gains, the materials used, and the lack of sustainable and recycling options have the cycling industry locked into a linear economy. The industry, like most, is sustained by sales, which in turn rely on new products with little consideration for end-of-life product recycling or long-term durability and repairability. There are, of course, incremental performance updates with each new product generation, but increased sales are almost always the primary goal. Making our bikes, the sport, and the industry as green as the activity itself should be a primary goal for consumers, the UCI, and manufacturers alike. Unfortunately, sustainability is not only rarely on the agenda, it’s often impossible in the current market.

Yet, the longer sustainability isn’t topping engineers’ design briefs, the more it needs to be topping everyone’s design briefs. Even a few manufacturers here and there going all in on sustainability isn’t enough, and arguably, none can risk being the first to boldly go where the planet needs us all to go, for reasons that we will lay out later. So what to do? What one single entity could motivate and enable the entire cycling industry to become much more environmentally friendly?

The answer: The UCI and its rules.

The UCI recently introduced an equipment register ahead of this year’s Tour de France and Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift. The stated aim of the new Equipment Register Process (ERP) is to ensure “fair and equitable access to equipment” for all. Combine that register with a few tweaks to the UCI’s frame approval process, and you might have yourself a set of technical regulations that not only provide that level playing field but, much more importantly, make for a much greener industry with more durable, serviceable, and properly recyclable bikes.

Where we are now

A large proportion of the cycling industry is driven by sales, new products, advertising, and growing a brand’s market share. It feeds on our desires to have the latest and greatest nice stuff using pro teams as moving billboards advertising some variation of the “lighter, stiffer, more aero, and more compliant” mantra. The result is new and incrementally improved frames and bikes every three to four years for a given chassis, wheel, or groupset at best or every couple of years at worst. Almost every new product is developed with improved performance (and sales) as the KPI, with little or no thought given to sustainable manufacturing, a product’s lifecycle, and particularly what happens to it at the end of that lifecycle.

It’s a never-ending rat race on a race track paved with dollar bills. So far, us rats have demonstrated incredible endurance and a love for new stuff, but dollar bills make for a terrible surface. Eventually the market will stop growing; arguably, it already has. The mass production of bikes, the ever-decreasing cross compatibility, and the ever-shortening product cycles seem to me a house of cards almost certain to collapse at some point.

But, what if, and bear with me here, we could avoid that card house collapse if something other than weight, stiffness, compliance, and aerodynamics became the goal? What if new cycling products could be every bit as fast, but the goal was to create them in a sustainable way? And what if that happened due to a simple tweak to the UCI rules, which created a ripple effect that ultimately led to more durable, serviceable, and recyclable bikes sold through a business model less dependent on impossible growth targets but instead guaranteeing recurring revenue for brands? Doesn’t that sound like a maximal gain for all?

It’s an unlikely dream, given manufacturers are more or less hamstrung right now, tied to the existing model with little incentive and only risk in entertaining even a notion of change. Take the performance road sector for example. “Race on Sunday, sell on Monday” is a model that’s worked for years, and I sure as hell wouldn’t deviate from it if I were a CEO answering to a board and shareholders.

“But it’s not an impossible dream”

Erik Bronsvoort

But it’s not an impossible dream according to Erik Bronsvoort, co-author of “From Marginal Gains to a Circular Revolution: A Practical Guide to Creating a Circular Cycling Economy” an excellent book on how and why the cycling industry should become more sustainable. It was a conversation with Bronsvoort on the eve of the Tour of Flanders that became the stimulus for this article.

Bronsvoort perhaps summed up the enormity and the potential of a new more sustainable model for the cycling industry best in his book: “Imagine a bike that has been made from plant-based materials or recycled and reused parts.” At the end of its life, “You no longer discard it as if it were a piece of rubbish, but return it to the manufacturer so that parts and materials can be reused to make new bikes.”

“Imagine a bike that has been made from plant-based materials or recycled and reused parts.” At the end of its life, “You no longer discard it as if it were a piece of rubbish, but return it to the manufacturer so that parts and materials can be reused to make new bikes.”

Erik Bronsvoort

“Nice thought,” I hear you say, “but that’ll never happen.” On our current trajectory, you are right. But the UCI has the power to reset the entire sport on a new trajectory. Here’s how:

A role only the UCI can play

Somewhere along the way of researching this article, I realised the UCI has the key to motivating the industry to be more sustainable and develop a circular economy. In fact, it already exists: the UCI Frame Approval Process.

The frame approval process has always struck me as quite the oddity. The process only exists to ensure frames –and by extension bikes – conform with an ideal the UCI has decided bikes should look like when used in UCI-sanctioned races. The UCI-approved sticker on your bike merely confirms your frame complies with the UCI competition regulations, which, according to the UCI’s Lugano Charter, are designed to “assert the primacy of man over machine.” To be absolutely clear, the UCI frame approval process is largely an aesthetic standard, not a safety one, and there are no safety elements within the frame approval process.

However, thanks to this frame approval requirement and the UCI’s separate commercialisation rule (stating all bikes used in competition must be available for public purchase), almost every road bike for sale in our local bike shops are approved for use in UCI-sanctioned events. In other words, we all get UCI regulation-compliant – and, thus, competition-approved bikes – regardless of whether we race UCI events or not, highlighting just how successful the UCI’s frame approval process has proved.

So, what if the UCI used its approval process to mandate more sustainable bikes and a more sustainable sport? Rather than just solely mandating aspect ratios and angles, what if frames had to meet certain sustainability parameters before they were approved for use in competition? If the bikes the pros ride must be more sustainable and repairable, and those bikes must be for sale to you and I, could mandating the pros ride more sustainable bikes provide the same knock-on or trickle-down effect we saw with the existing frame approval process. Could the UCI indirectly, but effectively, mandate that all road bikes are manufactured in more sustainable ways with environmentally friendly materials and manufacturing methods at the heart of a model with sustainability and a circular lifecycle as the key goals?

But what rule changes and what updates to the frame approval process could ignite such a fundamental shift for our entire sport? I thought you’d never ask; here’s a list I prepared earlier, which focuses on sustainable materials and uniform standards for component compatibility. Short it may be, but, admittedly, no doubt implementing it would prove incredibly complex. Still, one might have said the same before the initial frame approval process was introduced, and the rationale for a sustainability approval process is arguably much more sound and essential.

New regulations:

- Increase the minimum bike weight by a minimum of one kilogram. (bear with me)

- UCI/Teams to RFID tag all frames and components for spot checks throughout the season.

- Only frames and wheels manufactured with natural fibre composites/biobased materials will be approved for UCI-sanctioned events.

- Mandate on-bike smart sensors to measure usage and wear.

Frame and wheelset approval process updates:

- Include a mandatory bottom bracket standard within the frame approval process.

- A brake mount standard.

- Fork steerer shape and dimensions.

- Handlebar and/or stem clamp dimensions.

- Seat post shape and dimensions.

- Hub bearing dimensions.

- Thru-axle, dropout, and quick-release dimensions.

- Equipment allocation restriction for WorldTour teams with strict penalties for requiring additional.

- A freehub body standard.

Fairytale stuff, the lot of it! But hear me out. Considered in isolation, many of these proposals seem pointless acts of Luddism, but each is an essential piece in a bigger sustainability and circular economy picture. Together, these new rules and standards could prove a powerful tool in revolutionising our sport and the industry.

Key to a sustainable cycling industry is more durable bikes made with reusable materials. Bikes that go back to the manufacturers for repurposing into new bikes at the end of their life cycle rather than into landfill as is currently the case. All these proposed rules are interconnected, and each is essential to each other’s success.

You want to make bikes … heavier?!

Take frame weight and our current reliance on carbon fibre. Undoubtedly, carbon fibre has revolutionised our sport, but this wonder product is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, carbon has enabled manufacturers to produce lighter, stiffer, faster, and more intricate frames than ever imaginable. But on the other, carbon is extremely difficult to recycle or repurpose. Beyond gathering dust or being down-cycled into a fancy lamp, the all too-easily broken carbon frames we all know offer little future potential beyond a fancy lampshade or landfill filler at the end of their bicycle life-cycle.

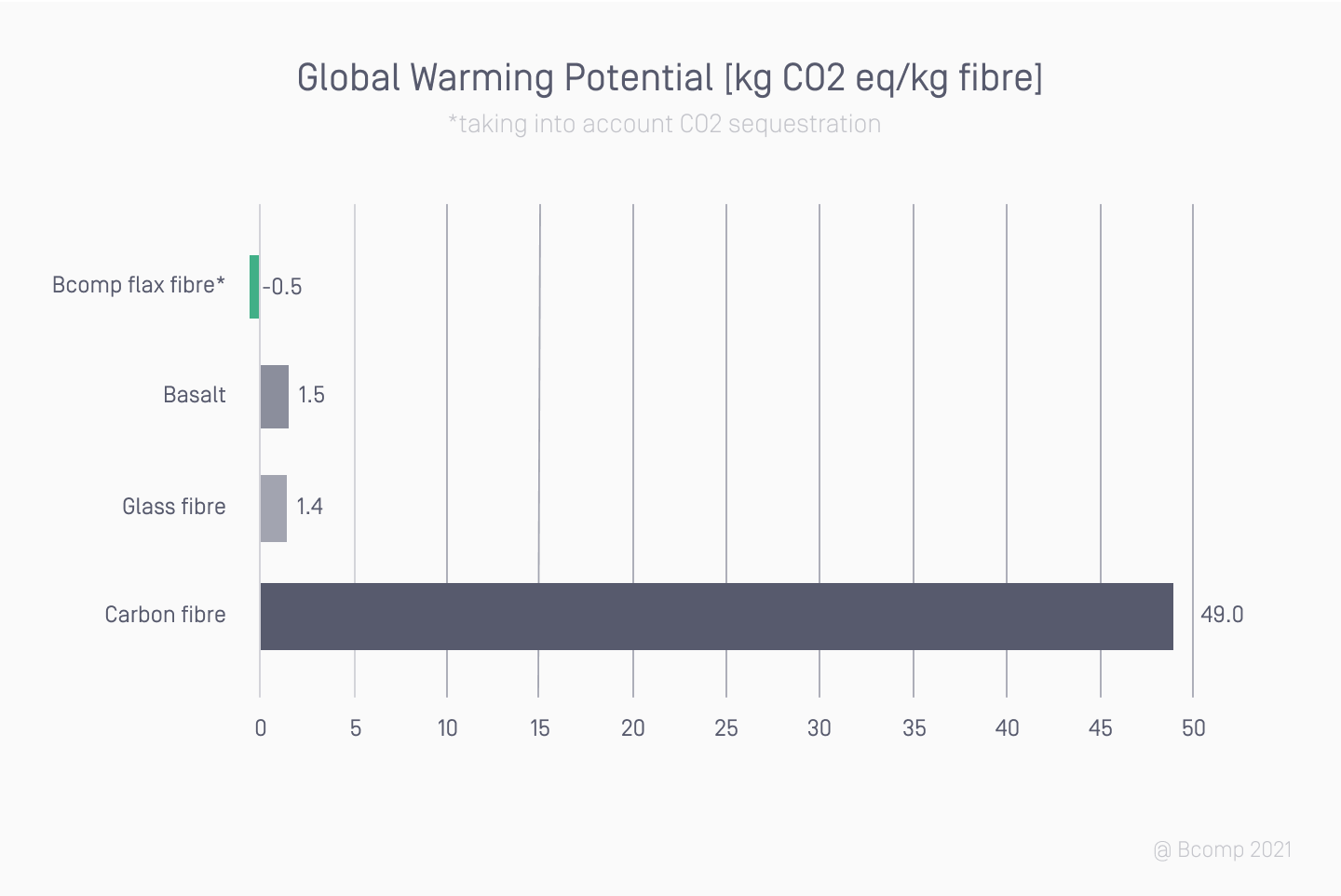

The good news is that natural alternatives are emerging, such as so-called natural fibre composites or bio-composites made with bio-fibres. Bio-composites are similar to common composite materials, such as carbon fibre, in that they are a composite of resin and fibres. Crucially, though, the fibres used in bio-composites are derived from biological origins, mainly flax, corn, cotton, etc. The development and use of bio-composites are rising due to their renewable, recyclable, biodegradable and cost-saving potential compared to carbon fibre. In fact, a hectare of flax plants, which simply grow in fields, can absorb up to 3.7 metric tonnes of Co2 per cycle and convert it into oxygen while growing, and flax can be used in crop rotation programs. In simple terms, think the opposite of carbon.

Better yet, bio-composites are not just a pipe dream. They are already widely used in many sectors, including automotive, marine, and motorsport, including Formula 1, the pinnacle of world motorsport. F1 isn’t exactly known for its cost-cutting measures or environmentally friendly endeavours, so why use bio-composites? Well, for one thing, F1 teams like bio-composites, because they offer improved vibration damping over traditional carbon fibre, a claim that will surely catch many cycling engineers’ ears and imagination.

Furthermore, flax fibre is effective. Ycom, an advanced technology company specialising in motorsports and lightweight composites, developed a Front Impact Absorbing Structure (FIAS) crash structure using AmpliTex, a flax fibre material developed by Swiss company Bcomp. Until the Ycom project, natural fibres had only been used in non-structural motorsport components. But Ycom tested its structure at an FIA-approved testing facility, returning “excellent results” and demonstrating “desired crash behaviour” in line with a crash structure manufactured with carbon fibre, and in doing so demonstrated natural fibres’ effectiveness in structural and safety-critical parts. Better yet, the flax fibres’ very nature means the material doesn’t shatter and splinter when broken like carbon.

In summary, flax fibre is said to be stronger, cheaper, and easier to use in manufacturing than carbon fibre and up to five times better at vibration damping.

So, if natural-fibres are cheaper, more environmentally friendly, offer improved damping, and are just as strong as carbon fibre, why haven’t we seen them used in cycling? The answer is twofold. First, and perhaps most surprisingly, bio-composites such as AmpliTex have already made their way into the cycling industry. Unfortunately, it is usually only as concept products, such as German brand Ergon’s SR2 BioComp Concept Saddle, developed, again, with Bcomp, and which won awards as far back as Eurobike 2012. Bcomp was again involved, along with several academic partners, in 2015 in developing a fully recyclable flax fibre saddle. Going back further again, there was the 80%-flax-framed, biodegradable Schwinn Vestige town bike released in 2011, while in 2008 Museeuw Bikes used a carbon-and-flax fibre blend in their MF-seriesframes in a bid to harness the improved damping flax fibres offer.

But it’s perhaps hobby builder David Protheroe’s British start-up, Revolucion Frames, who has best demonstrated flax’s potential in cycling. Protheroe actually produced several frames made almost entirely with Amplitex flax fibre tubes and titanium lugs. Protheroe told Escape Collective he was initially inspired by Chris Calfee’s frames and Darren Baum’s geometries. Although he’s since abandoned the idea, Protheroe took Bcomp’s flax fibre, worked with a third party to roll it into tubes, and eventually produced lugged tubed frames. The frames were tested to EN14781 standards and passed, but that’s where the process came to a halt before he had a chance to explore his plans to produce flax fibre lugs. Still, Patrick Vuagnat, Sports and Leisure manager at Bcomp told us the company is already working with the cycling industry and we can expect blended flax-and-carbon fibre products again in the coming years.

But it’s not just a simple slam dunk for natural fibres. Stefan Christ, Head of R&D at BMC, told Escape Collective the Swiss brand had first looked into eco-fibres almost a decade ago, and although there are benefits, especially in terms of vibration damping, these come at the expense of stiffness, and it was impossible to decipher if the damping came from the flax itself or the decrease in stiffness.

Furthermore, these natural fibres lose some of their renewable and recyclable brilliance when encased in epoxy resin. The good news is biobased resins are emerging, and hence why our proposed rule changes include the use of said resins.

But perhaps the biggest obstacle to any mass uptake in the use of natural fibres is the added weight compared to carbon. The Amplitex crash structure, for example, is thought to be 40% heavier than similar structures manufactured with carbon fibre. That said, this weight penalty drops to around 9% in less safety-critical parts. As Protheroe explained, while carbon tubes can be as thin as 1 mm, he had to increase the flax fibre wall thickness to 3 mm to ensure the correct strength and stiffness. Eventually, Protheroe turned to wrapping carbon fibre in flax fibres for a lighter solution with the same damping benefits, but at the expense of the sustainability aspect.

As significant as a shift to bio-fibre could be, and the many benefits manufacturing with such materials could offer, it’s unlikely any brand will voluntarily make its bikes heavier without guarantees the competition will follow suit. That’s why our first proposal is to increase the minimum bike weight. Give brands the freedom to choose natural fibres by forcing them to make heavier bikes. As BMC’s Christ explained, “with our ambition to create the best performance bikes and the market being very weight-driven those materials are not applied by BMC yet.”

How mandated standards help

To its credit, carbon fibre is pretty durable. I recently rode a 20-year-old Time VXR that felt as good as it probably did the day it was first built. It’s usually crash damage that spells the end for a carbon frame, and even then, many can be repaired. Unfortunately, though, it is often the case that a frame is deemed obsolete due to changing standards rather than actually reaching the end of its life cycle.

Frames can become outdated in two ways. First, the optimisation rat race leaves riders feeling their older bikes are holding them back, and an upgrade is required. Second, frames can become outdated because there simply isn’t a stock of compatible parts available to fix simple mechanical breakdowns.

Furthermore, these components tend to make up the vast majority of a bike. Take the simple issue of mass: a road frame typically only accounts for about 1 kg of a 7-8 kg bicycle; everything else is components. Unfortunately, the components also tend to be the least-durable items, so there is a significant environmental issue here (aluminum production from new materials, for instance, is a dirty, energy-intensive process). Regardless of why components have such short life cycles, perfectly good frames can end up in the scrap heap if a manufacturer no longer produces a proprietary component for an older frame or standards have changed and a compatible replacement is no longer available.

It’s for this reason we have included our proposed new frame and interface standards. These frame approval updates are based on ensuring compatibility across multiple frames into the future. Take bottom bracket standards for example: with all the back and forth over the past decade or more, almost every manufacturer has gone from good old-fashioned threaded bottom brackets to a variety of press-fit options, and now back to threaded. If the UCI was to mandate the use of, for example, T47 threaded bottom brackets in its frame approval process, manufacturers could and would make all pro-level bikes to this standard. The UCI’s commercialisation rule would effectively mandate all consumer road bikes are made to the same standard and hence one bottom bracket standard for all. I bet you like the sound of that.

The same logic applies to brake mounts, fork steerers, handlebar or stem clamp dimensions, seat posts and hubs, even freehubs. Despite the absurd number of varieties and proprietary designs that currently exist, there’s very little reason the UCI couldn’t mandate one single standard or just a set of dimensions for each of these interfaces, provided manufacturers were given adequate notice. The short-term result would be much greater compatibility; longer-term, such standards could ensure new parts are always backward-compatible, all but ensuring good frames never go to waste.

There is, though, an even greater hope with our proposed interface standards. If interfaces are identical across the board and bike owners are no longer beholden to proprietary components, that could translate into more options for consumers from more manufacturers. More choice could mean a price war, but it could also mean customers might naturally lean toward the most durable components available, motivating brands to produce more-durable products. Again, think bottom brackets: if any manufacturer’s option fits your bike, will you buy the less-durable bottom bracket or the bottom bracket known for its durability? In other words, the UCI frame approval process could indirectly ensure the components manufacturers also put a renewed focus on producing the most durable and sustainable products possible.

Equipment restrictions for World Tour teams?

Finally, we mentioned an “equipment allocation restriction” (EAR) proposal. As good as modern bikes are, they are also incredibly fragile. One crash, a rough baggage handler, or an over-tightened clamp can destroy an entire frame, wheel, or critical component. Currently, Some of the top WorldTour teams require as many as 300 frames every season, more if the manufacturer has multiple frame offers. For example, Trek-Segafredo has the Trek Madone, Emonda, and Domane to choose from for road stages and the Speed Concept for time trials. On the contrary, a team like Ineos Grenadiers just has the Pinarello Dogma F for road and the Bolide F for time trials.

Tied again to the increased weight limit, we believe a strict limit on the quantity of each critical equipment component (handily already defined by the UCI in its Tour de France Equipment Register Process earlier this year as framesets [or modules], wheels, road and TT handlebars, and TT extensions) teams can use per season could both force and enable manufacturers to produce slightly heavier – but crucially more durable – products.

If the UCI decided teams had, say, half as many road frames per season at their disposal, that is still three to five frames per rider. If the increased weight presumably required to make a more durable frame was negated by an increased minimum weight limit and the penalty for requiring additional components sufficiently stringent, might we see more durable frames?

How could such a restriction be enforced? My suggestion is RFID tags, which, admittedly, seemed a little ridiculous until the UCI unveiled its TDF Equipment Register Process, which requires teams to have every frame it wishes to use in the Tours de France RFID tagged in advance. The UCI conducted random checks during the Tour and warned untagged frames would not be permitted for use in “Le Grand Boucle.” It seems to me the same tags and process could be applied pre-season and similar rules applicable throughout the season.

Again, motorsport is proving what is possible here. Remember that flax fibre crash structure mentioned above? If natural fibres are adequate for use in motorsport crash structures, at least by my brain’s model of the transitive property, that means they could be used in manufacturing more durable bike frames also.

Stifling innovation?

Admittedly, there is a lot to iron out in this proposal, not least of which is whether a single bike weight limit is fair in a peloton of very differently sized riders or how to ensure teams wouldn’t risk racing damaged bikes, but arguably, it could offer a better way to ensure the UCI’s desired goal of “fair and equitable access to equipment.” Teams and manufacturers certainly wouldn’t like it, but they already don’t like the current rules; regardless, both parties usually tend to march to the UCI’s beat.

But wouldn’t all this just stifle innovation? We might bemoan the never-ending churn of new bikes and updates, but for many, myself included, the latest tech is as exciting as the racing itself.

… design has a huge impact on the entire lifetime of a product

Erik Bronsvoort

As Bronsvoort explains in his book, “… design has a huge impact on the entire lifetime of a product.” Until now, designers have innovated in pursuit of improved performance. New sustainability regulations could be seen as stifling innovation, but I prefer to think they could actually promote innovation. Our proposals don’t tell manufacturers or designers what they must produce, just the parameters within which they must work. Better yet, rather than questionable innovation chasing ever-decreasing marginal gains, manufacturers are actively encouraged to innovate in pursuit of new sustainability goals under these proposals.

The new challenge will be to create the fastest, most durable, and sustainable bikes. If anything, it could prove more exciting as designers and engineers are handed a whole new target to aim at.

Wait, what about the industry?

Won’t the industry go broke if it can’t sell us new bikes and lock us into their components? Not if Bronsvoort’s goals for a new business model can be realised – which our proposed UCI regulations might just make it possible. In fact, as Bronsvoort sees it, there is a huge opportunity the industry cannot afford to miss, explaining ”pay for performance”, or perhaps “leasing” to you and me, is the cycling industry’s future, provided many of the aspects we have already discussed are realised.

As mentioned earlier, growth is vital to the linear economy the sector currently operates in, where selling more and more products is the only way to increase profits. But uninterrupted and never-ending growth is impossible, as is evident by the current market decline and the rumours of some brands struggling with as many as 800,000 bikes in overstock. Furthermore, if the marginal-gains rat race and the resulting recurrent price increases aren’t enough to stifle sales, then the cost-of-living crisis many are experiencing in 2023 will surely have an additional impact. What every industry wants is guaranteed and recurrent revenue streams, and Bronsvoort suggests “pay-for-performance” provides such a stream.

Bronsvoort combines the groupset and wheelset into a powertrain pay-for-performance package. The model is built on a subscription service to access the performance (or spec) you desire and classifies the bike into four categories: the platform/frame, the powertrain (wheels & groupset), the consumables (brakes, tyres, bar tape), and the computer.

The frame is the core of any bike, and, along with our version of the UCI’s new frame approval process, there is now a defined interface for each of the other three component groups to mount to. This is the frame approval process’s true value: it ensures compatibility, adaptability, and upgradability. This is crucial in ensuring the market-wide adoption of such a program.

Furthermore, the bio-based emphasis should ensure every frame has an end-of-life purpose. Old bikes ending up in landfills is no longer acceptable, and Bronsvoort suggests that end-of-life purpose should be the responsibility of the manufacturer. To that point, Bronsvoort suggests a successful change in the business model would also include a “buy-back scheme” where manufacturers pay consumers for frames to use in a “pre-used” program or recycle the materials into a new frame at the end of their life cycle.

Keep dreaming, that’ll never happen

Does this seem ridiculous? It already exists in other industries. On Running offers its Cloudneo running shoes in its Cyclon program. Cyclon is a shoe subscription service that provides recyclable shoes in a circular model: the exact pay-for-performance approach Bronsvoort advocates. The end-user/runner never owns the Cloudneo trainers, they simply pay for their use with monthly payments. When the shoes reach the end of their life cycle, On sends the runner new trainers.

On the one hand, it seems like a trap to sell us more trainers; on the other, for the avid runner who needs new trainers anyway, it’s a way of ensuring they have new trainers and the old ones are actually recycled into new trainers. Better yet, the runner only pays for the trainers if they are running, and when the trainers are no longer up to that job, they become the manufacturer’s responsibility.

In having the athlete return the trainers, On Running takes responsibility for what happens to the trainers at their end-of-use, cleaning, shredding, and recycling the old trainers back into raw materials to make new trainers. It cuts down on waste, creates a circular economy, and presumably best of all for On, the Cloudneo runner ensures a recurrent revenue stream.

A bike is not a pair of trainers, though, and with multiple manufacturers’ products coming together to make a complete bike, such a model is far from as simple to implement in cycling. Bronsvoort’s proposed model still sees the consumer purchase the new or used frame. As Bronsvoort sees it, the customer would lease the additional components required in somewhat of a return to customer spec and built bikes rather than the proliferation of OEM spec bikes of recent times.

How would that work? The powertrain (again, the wheels and groupset as Bronsvoort sees it) is perhaps the most complex group of components to integrate into any lease-style program. These components are increasingly more expensive and often less durable than ever. However, for most, the groupset of choice has little to do with aesthetics. Many riders simply want a groupset that works and lasts. Bronsvoort suggests this means consumers are more willing to simply pay for the performance level they require when they need it.

This pay for performance might come in the form of a monthly payment, with various levels to choose from and maintenance included. Riders could even upgrade for special events, pause the subscription during downtimes away from the bike, and all the while, the drivetrain is the manufacturer’s responsibility. If it stops working, the rider simply gets a replacement.

This model would incentivise manufacturers to develop almost bulletproof components to minimise maintenance costs and our proposed increased weight limit might again provide the space for manufacturers to do so. A win-win, reducing waste and time off the bike for riders, albeit at the expense of super-lightweight bikes.

But why would a powertrain manufacturer entertain such an idea? Again, it comes back to the guaranteed and recurrent revenue stream. So long as a manufacturer can deliver on the customer’s demands, they are assured of the rider’s monthly payment. Of course, pricing will be critical, but with the ever-increasing prices within the bike industry, the cynic within me might conclude the industry is already prepping the market for an automotive-style leasing model. Does leasing, monthly payments, used market, and maintenance-inclusive packages sound familiar? If you’ve ever bought a car from an authorised dealer, it probably does.

While the “pay for performance” model Bronsvoort lays out has potential, arguably, I can’t help but feel having manufacturers lease complete bikes might prove the easier option. Bike leasing options are on the up, with Lease-a-Bike reported to be taking over secondary sponsor position at Jumbo-Visma, and other such companies springing up around the globe. In fact, according to Velopass, makers of that theft and sustainability tackling sticker we saw at Eurobike, lease bikes already account for roughly 70% of the new bike market in Belgium. Bikeflex.co.uk, co-founded by former road pro-Russel Downing, is a relatively new UK-based lease company that offers road bikes, e-bikes, and cargo bikes on monthly plans. While the goal is to make premium bikes more affordable for all, if successful, the model could prove bike leasing as a viable option in the UK where it has struggled until now.

The entire proposal is not without problems. I’ve only looked at the road section of the market here, a segment that has arguably peaked as more and more turn to gravel and mountain bike riding. Furthermore, the UCI doesn’t have a frame approval process for any discipline other than road, and shows no signs of introducing one, nor does anyone want them to do so.

Again, the motorsport sector of the automotive industry is arguably leading the way here. I’m not for a moment suggesting the automotive industry has suddenly gone entirely green. That said, some of the sustainable alternatives being developed in these automotive brands’ motorsport departments will trickle down to the cars you and I drive on the street.

Furthermore, such a “pay-for-performance” model could arguably accelerate turnover and disincentivize consumers, maximising the use of a product. Bronsvoort argues an industry buyback scheme will ensure a circular economy and ultimately reduce wastage as younger used bikes are recirculated into the market while the oldest bikes are upcycled into new bikes. But that still means producing more bikes and making them easier for the customer to change in a pretty stagnant market. That’s why actual recyclability and up-cycling will be key, not just some end-of-use down-cycling tick-box exercise.

In the short term, arguably, the biggest obstacle to implementing such a program might actually be the used bike market. Currently, bikes depreciate at such a rate they often are worth more to the rider in sentimental value than in the second-hand market.

But could that be the most tangible benefit of this entire proposal? Would robust and serviceable bikes prove more desirable and valuable in the long term. More desirable bikes better retain their value and, as such, are much less likely to end up in landfills. Cars and other vehicles are far from perfect, but on average, even the cheapest of entry-level cars typically serve their purpose for much longer than the best top-of-the-range bikes.

If our cars can sustain thousands of kilometres between services, retain their value relatively well, move from user to user for years on end, and all the while have the manufacturer incentivised to buy back in order to re-sell to the same customer, couldn’t our bikes work the same way?