We spoke to Erik Bronsvoort of Circular Cycling to learn more about his efforts to promote sustainability and a circular economy in cycling

By Tom Hallam-Gravells at GCN

Erik Bronsvoort promoting a ‘circular revolution’ © Erik Bronsvoort / Circular Cycling

At face value, bicycles are a green mode of transportation. Governments around the world have turned to them as a method to clean up cities and curtail the increasingly damaging effects of global warming, encouraging citizens to swap their gas-guzzling vehicles for ones run on reliable leg power. It has spawned better cycling infrastructure, cycle-to-work schemes and a thriving second-hand bike market, all of which contribute towards a more sustainable future.

There’s a big ‘but’ here, though. Dig a little deeper and the green credentials of the cycling industry become a little murkier. For many years, the industry has overlooked the sustainability of production, the materials used and the transportation of goods, instead hiding behind the face-value sustainability of the bicycle.

A shift change has recently emerged, with brands showing a greater awareness and taking more ownership of their environmental responsibility, and the results of this were on display at the Taipei Cycle Show, where sustainability was a theme of the week. Multiple companies took the opportunity to present their approaches to sustainability and they were joined by experts in the field, who were there to spread a greener message.

For Erik Bronsvoort of Circular Cycling, this message was one of a ‘circular revolution’. A Dutchman on a mission to clean up cycling, he has set about educating brands about sustainable practises, with the aim of transforming the cycling industry through the concept of a circular economy.

His work and ideas are already taking root but there are still many obstacles to overcome and lots of progress to be made across the industry, as we found out when we caught up with him in Taipei.

Cycling’s sustainability problem

As a consumer, it’s often hard to gauge the environmental impact of a product. Many brands aren’t too forthcoming about their carbon footprint or the green credentials of the materials they use.

Avoiding accountability for sustainability has also been relatively easy, mainly due to the bicycle’s symbolic status as a green alternative to motorised transport. That green label has become a mask which has enabled the industry to hide its less sustainable practices, and ignores the large recreational side of the industry.

“The cycling industry has always been hiding behind the fact that the bike is the sustainable alternative to the car, which is definitely true if bikes and e-bikes replace cars, but then there’s the whole sports side which has nothing to do with sustainability,” Bronsvoort explained.

“The leisure business is making toys [recreational bikes], and we don’t replace cars with the toys. In fact, we put them in the car like I did a few years ago, and I still do, to travel to the mountains to do some riding there.”

Worse still, most recreational bikes, and bikes in general, are destined for landfill at the end of their service lives. Consumers have a level of responsibility to recycle their bikes, but most bikes simply aren’t designed to be recycled, which places the onus back on the manufacturers.

Erik Bronsvoort during a workshop at the Taipei Cycle Show © Erik Bronsvoort/Circular Cycling

Concerns over this non-sustainable model prompted Bronsvoort to found Circular Cycling in 2018. What started out as an up-cycling project focused on turning neglected bikes into sellable models soon took on a crusade to transform the industry from a linear to a circular economy, culminating in the release of the book, entitled ‘From marginal gains to a circular revolution’, that he co-authored with Matthijs Gerrits.

Bronsvoort has become a one-man preacher who works closely with many top brands to help them integrate more sustainable practices, based around the aforementioned circular economy. At the Taipei Cycle Show he was invited to host a workshop on the subject.

A ‘circular revolution’: First scoffed at, now spreading

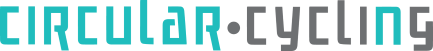

The concept of a circular economy is simple and can be gleaned from its name. Rather than the linear model that the industry has traditionally followed – where products take a depressingly familiar route from production through to the piles of landfill – it revolves around the reuse and regeneration of products.

This most obviously means creating products and using materials that can be recycled, but there’s also a focus on the production process and creating bikes that are of high quality with durable parts that don’t need to be regularly replaced.

“A lot of companies don’t think about the user, they think about ‘we need a shiny product in the shop, sell as many as possible and if it breaks down, not a problem because the customer will come back and buy another product’,” Bronsvoort said.

“But that’s not the way we should be designing products. We should really be designing from a user perspective. The user doesn’t want a creaking bike, they don’t want to replace chains and chainrings and all sorts of other stuff, they just want a bike that runs very long.”

In a circular economy, products are reused, which is also relies on the materials used and the production processes © Circular Cycling

Preaching this more user-friendly model isn’t easy. Cycling companies, like in other industries, are ultimately profit-driven. It’s perhaps not too surprising that Bronsvoort found himself swimming against a torrent of opposition at first.

“I remember very well the first time we were on the stage about five or six years ago, people were looking at us like ‘these guys are nuts, they must be complete idiots. Why does the bike industry have to do anything but also how can the bike industry do things different?’” he remembers.

Opposition to his ideas has slowly broken down, though.

“The more and more people we get involved in the workshops and get them excited, the more of a change you see. So some of the bigger brands you see like Trek, Canyon, they’ve been training dozens of people in the company now. You really see them talking to each other, and coming up with new ideas, and also inspiring people higher up in the company to take this stuff seriously.

“And slowly but steadily, things are changing. I mean five years ago, there was no way I could get in contact with Taipei Cycle or the Taiwanese cycling industry, and now I get invited to run a workshop here.”

Greenwashing remains a problem

Much of this progress was on display at the Taipei Cycle Show where the vast halls were filled with tales of sustainable products and processes. Not everyone’s sustainable claims stack up to the weight of scrutiny, with greenwashing an ever-present shadow.

It is another particularly hard obstacle for consumers to navigate.

“Nobody’s perfect but a lot of companies out here claim to be sustainable or green,” Bronsvoort reasoned. “I think it’s a good start if you place solar panels on the roof of your factory, but it doesn’t mean that you are sustainable.

“Big claims are being made for tiny steps. And that’s a big problem because consumers will not be able to identify what is a really sustainable product and what is just a claim.”

It is equally important to acknowledge that no brand can claim to be totally sustainable yet, but there’s nothing wrong with brands sharing their legitimate progress towards that end goal. After all, a truly circular cycling economy remains a far-off dream, even with significant industry buy-in.

“At the end of my workshop, I always tell everyone, if we want to get properly circular, then we have to have an industry where there’s no more use of finite resources, there’s no pollution anywhere in the supply chain – in the use or end-of-use phase – or there’s no waste. That would be a truly sustainable bike industry.

“There’s no way that we could ever get there within the next 20 to 30 years.”

Pro cycling’s sustainability problem

A big obstacle still in the way of a circular cycling economy and sustainability, in general, is professional cycling. The unsustainibility of the sport is apparent and hasn’t escaped scrutiny over the last few years.

Critics have taken aim at the significant air mileage of teams, not to mention the swarm of vehicles that buzz to every corner of Europe, and across the globe, racking up significant carbon footprints in the process.

Less scrutinised but just as important is the role pro cycling can play in the sustainability of bicycle production, specifically if the sport’s governing body, UCI, takes a hardened stance on the subject.

Brands are in a constant arms race to produce the most aerodynamic, lightest and stiffest products, which are all marketing buzzwords most cyclists will have encountered numerous times. Most of this is driven by pro cycling and the constant need to find a new marginal gain. Chasing this all-out performance often isn’t compatible with sustainability.

Pro cycling has a significant carbon footprint, partly due to the fleet of cars that attend races © Getty Images

For Bronsvoort, the UCI is well-positioned to change this approach by enforcing new rules, with scope to learn from other sports, such as Formula One.

“I would really like to encourage the UCI to say ‘we use the pro peloton as a platform for innovation, on sustainable and circular materials’. So, they could set up rules to say we’re going to raise the minimum weight limit from 6.8kg to say 8kg. There’s a lot of room for experimenting with different materials, like bio-based composite materials, which are already out there, already being used in Formula One and in sailing boats.

“Could you imagine what would happen if you do have the space to start innovating on a new generation of materials and the UCI says you need to have at least 50% recycled content or 50% bio-based materials, and all of the components on the bikes need to be properly recyclable, so they don’t end up in a landfill or an incinerator, but can be brought back into the production process?

“Then there is the durability part, so if you could limit the number of bikes that a team could use each year, like what happens in Formula One with the number of engines or tyres you can use in a race, it really would spark a wave of innovation towards making more durable products.”

This innovation would have an impact on everyday consumers too, as the road bike market specifically is, to a large degree, shaped around the needs of pro cycling. Even lower-end models take many of their performance cues from WorldTour-level models, while some consumers naturally want to emulate the pros in the only way that is possible to them, through tech.

If pro bikes were forced to become more sustainable, this would trickle down through the industry.

Progress made but ‘circular revolution’ still in its early throes

If you’ve taken a scan around the number of sustainable products currently available, you could be forgiven for thinking that progress in the ‘circular revolution’ has been slow.

While there are some notable exceptions, such as Vittoria’s new Terreno gravel tyre which won the Green Award at the Taipei Cycle Show or AGU’s undyed collection of clothing, there remains a meagre number of products that can rightfully hold aloft the sustainable tag.

Vittoria’s new Terreno tyre, which hasn’t officially been released just yet, won the green award at the Taipei Cycle Show © GCN

This isn’t indicative of a lack of buy-in but reflects the fact that the industry is still in the early phases of its journey to more sustainable models.

“For sure [the industry has made progress], there’s a number of big brands working really hard and you don’t see that many products being launched yet, because they’ve only started working on this for two or three years, so it takes time until they hit the market,” Bronsvoort explained.

“But it’s definitely happening and I think we’re going to see the next wave of innovation. It’s not about the marginal gains any more, so we are more aero than our previous generation. No, it’s going to be about, ‘look at us, we’ve been experimenting with these new materials and they’re way more environmentally friendly than the competition’.”

And the Dutchman remains confident that the industry is on an exciting path to better sustainability: “I think it’s going to be a really fun period in the next few years to see new innovation.”

Originally publish on GCN.